I split the trip up into three days. Day one took me from my home in Provo, Utah to San Francisco, where I stayed with a friend who lives in the city. Day two, I traveled from San Francisco—crossing the golden gate bridge on my way out of the city—to Arcata, where I stopped at an ex-girlfriend’s family cabin near the sea. I’m now on day three, in the middle of Redwood National Park between Arcata and Cottage Grove, Oregon where I will be spending the next two months as an intern at a small intentional community called Aprovecho Education Center. I wind and wane through sun sparkled and shade darkened corridors of green shaggy moss that repel from old growth Redwood trees. Clusters of ferns nestle up to their massive trunks and listen to the wind whisper through ancient branches.

It occurs to me. I am driving through a museum. A place set aside from intensive clear cuts and cancerous urbanism that rage only a few miles away in any direction. The rode was perhaps bored deliberately through the forest to reassure travelers and tourists that the system we are immersed in is working; that although we may be wreaking havoc in other spheres, this one was safe, true, “wild.” But maybe it simply reinforces the myth we tell ourselves over and over when we come to worship in these sacred groves; a myth that goes something like this: we are advanced humans, we are separate from nature, it is ours, we act as its benevolent protector, and whenever we preserve swaths of old growth forest and plaque them with names we are acting altruistically because these trees could certainly be converted into cash, the life blood of our economy. But we preserve them so that we have places to come and marvel at the nature we control, and because our strong economy gives us the privilege of doing so. This sad narrative means that nature’s primary value in its natural state is aesthetic, not as a support system and community.

I pull the car into a turnout and crunch onto the shoulder’s course gravel; my back bends as I stare upwards. I can barely make out the points of trees that make up the canopy. The lumpy forest floor is teaming with electric green life. I pick up a clump of green moss and moist soil and think to myself—I am a stranger here, a visitor, a tourist. The forest, though visible in form is invisible in function. I enter with no knowledge of its complex cycles or processes, its motion and change. It is inert, still, a painting on the wall that I am eager to capture with my camera for nostalgia, a mass of raw materials for my use and enjoyment but instead of being turned into toothpicks, this forest it is nothing more than a screen on my television or my passing car window that earns sighs and wonder and is then quickly forgotten, when we change the channel.

We destroy one part of the land for profit, and abandon another for aesthetics.

As I sway with the tight curves of the road that weaves its way though shaded asphalt and rugged coast line, my mind wanders. Is it foolish for me to wish that all forests looked this beautiful and supported flourishing human communities? Large corporations and their benefactor the state own millions of acres that could be under community control; communities that not only depend on the forest for their livelihoods, but see in the forest more than raw materials for conversion into cash and calories, they see it as part of their community. I imagine a small militia of men, women and children saying “ya basta” like the Zapatistas of Chiapas, Mexico, to the corporations that treat these majestic trees like corn and wheat. Not a cohort of ex-urban hippies like me, but people who truly understand the life and death struggle we are facing globally and locally. A humble band of poor, uneducated of indigenous peoples and white folk who decide to expropriate the forests from the tight fists of power, while huddled around clandestine camp fires, safe in the bosom of the forest. I chuckle to myself at the absurd romance of the thought and what a poor revolutionary I would make. I am afraid of violence in even the smallest doses, and the expropriation of a corporate owned forest would surly illicit a violent response, especially if we were armed, would they use napalm and destroy the forests further? Or would they surrender the land to the humble demands of community control and autonomy? The day dream is exciting to me and I readjust myself in the driver’s seat smiling to myself. The headlines, the electricity in the air of doing something so radical in a country so bogged down in the lies it tells itself. What if we could do it non-violently, I mean the Zapatistas don’t even carry real guns anymore. Expropriation…is that what it’s going to take to save the forests? Am I willing to fight? Is it even possible to make such changes through the system? If so I am certainly willing to try…

*****

I squat near a chopping block; smoke from the wood cooking stoves in the outdoor kitchen wafts and fades in the afternoon breeze. Today is my small group’s turn to cook the evening meal and I am chopping small pieces of wood to feed the fire boxes. As I chop and stack in mechanical motions, my mind and body begin to synchronize. I have been at Aprovecho Education Center for about a week as an intern and my soul is already full. My surroundings are pristine, not in the sense of a wild untamed nature, but because I am surrounded by a humanity that isn’t afraid of putting down roots. I am living briefly in what may be humanity’s natural habitat. Small groups of kin and friends, who cook for each other, work together, love and take care for each other, and make decisions collectively. We take our sustenance from gardens and the surrounding forests, build our homes from local materials and take responsibility for our waste. Yes, we even compost our feces here. It is not whisked away out of site and mind with one sterile flush, it stays with us and we are forced to deal with it. A strange idea at first, but one that relates to the root problems of modern society: dislocation from our bodies and the earth, and action without responsibility.

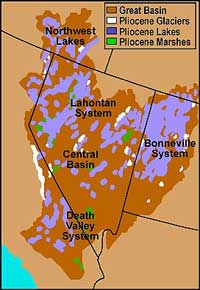

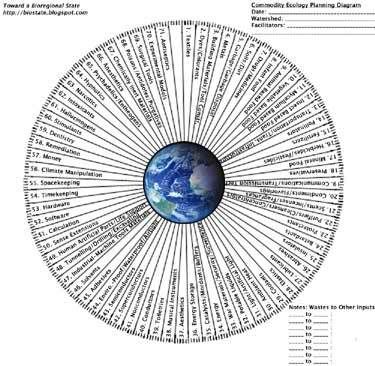

As I write these words, I am looking my dorm room window at the gardens, and the hornets that rise and descend from the roof. I am recounting these recent life experiences because I believe the time has come to shift our consciousness, our loyalties. Our cultural, political and economic institutions are at the breaking point and with the increasing scarcity of fossil fuel energy, may become obsolete. If we are to survive as a species, and if we are to continue to improve the quality of life for future generations, we must begin dismantling the systems of economic and political tyranny that are destroying the earth and its people. Paying attention to our bioregion is one way in which we can begin this transition. A bioregion can be defined in a number of ways, but the June Sucker Nation Refers to a very small region where the June Sucker flourishes, specifically the Utah Lake area and its tributaries. Our watershed is the most precious gift we have been given as earth stewards, and a gift that we must pass on to our children. As citizens of June Sucker Nation, it is our duty to ensure the health and security of our water source and the biotic community we share it with. This may mean limiting urban growth, planting trees, designating protection of riparian zones, and creating citizen-based watershed councils. But above all it means shifting our consciousness from that of state and national patriotism, to local and biological citizenship and stewardship.

As the lines on our maps begin to shift away from arbitrary political borders toward boundaries that make ecological sense, we will begin to revitalize our local political institutions with decisions that make sense at a local level. In this type of world, letting Wal-Mart into our community would be unthinkable due to its effect on our friends and neighbors with whom we interact and do business. Large, poorly planned, car-dependant, housing developments will seem ludicrous in the face of oil scarcity and the impending loss of farm land we will need to produce our food. The concept of Bioregional living is of course not new, it has been the underlying logic in most indigenous communities. For example, the native peoples of this region would never have damned the Provo River, because they depended on the annual rejuvenation of native fish species for their sustenance. But settlers to this region dammed it, and the fish died off in mass because their aim was not survival, but profit.

Though a total revolution of political consciousness may be our final goal, we can start much more simply by reading and understanding the history of our watersheds, our rivers, and our biotic communities. How many endangered species are there in our backyards? How can I create a favorable environment for native plant and animal species? What sorts of things can we do to ensure that the June Sucker continues to spawn naturally without the intervention of scientists? Where does my food come from? How much of my food can I reasonably produce on my property? Do I really need two cars? One? What are the mountains called around my house? Do I need the government to tell me that it’s not good to litter or dump motor oil in the drain? As we begin to ask ourselves these questions, our ability to act as free and creative human beings will coincide with the increased health of the ecosystem. Bioregionalism is not mandating change; it is working toward a “permanent culture”, creating it from the grass-roots and empowering communities to make their own decisions with the perspective that we are not nature’s masters but its brothers and sisters.

This is a photograph from historian D. Robert Carter's collection. It was labeled "State Mental Hospital". Which I believe you can see when you follow the rough line of structures and trees that mark the beginnings of Center Street. The hospital was one of the first buildings in Provo. If you visit their lovely grounds today you'll see a large plot that has never been touched. You'll also see a lot of deer and an apple orchard.

This is a photograph from historian D. Robert Carter's collection. It was labeled "State Mental Hospital". Which I believe you can see when you follow the rough line of structures and trees that mark the beginnings of Center Street. The hospital was one of the first buildings in Provo. If you visit their lovely grounds today you'll see a large plot that has never been touched. You'll also see a lot of deer and an apple orchard.